From the depths of the void a mighty bolide falls to earth — crashing into the waters it raises tsunamis, washing away trillions of microscopic lives. We are of course talking about a bathroom break.

A stool is only part digested food. The rest — around half — is made up of microbes, trillions of them.

An appealing but inaccurate stat suggests microbial cells in and on our body outnumber human ones by a factor of 10:1. But this isn’t correct. The correct figure is closer to 1:1. An average adult male is made of ~30 trillion human cells, and recent estimates suggest we also carry around ~40 trillion microbial passengers.

Our insides are a vast ecosystem, a terrarium of bacteria, fungi, and other microbes, and indeed a bowel movement is an environmental catastrophe, albeit a regular one (if you’re eating right). But where did all this life begin? How long has it been evolving, and how does it replenish?

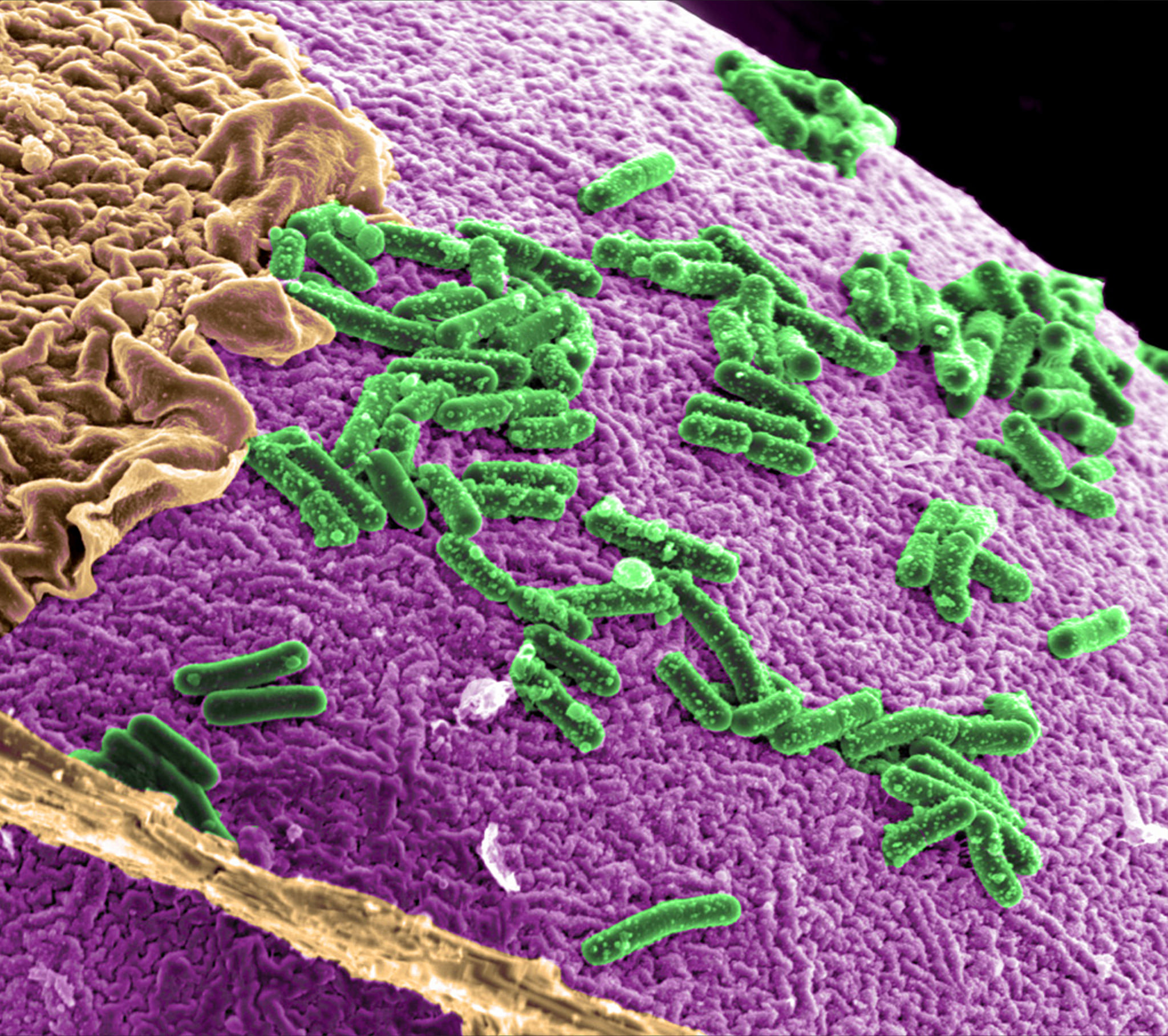

A human intestinal cell (violet) populated with its favourite single-celled compatriots, bacteria (green). Image: Pacific Northwest National Laboratory/CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In the beginning, before birth, our insides are almost completely sterile, a landscape formless and desolate. Our first dose of microbes comes from our mother. As we’re born and exit the vagina, less-so via Caesarean, we ingest our mother’s vaginal and faecal microbe communities. This ingestion is a starter or ‘mother of vinegar’ that seeds the life in our insides.

Babies born from C-sections have a different gut microbe community. During breast feeding their microbe community resembles not the typical faecal community, but that of the mother’s skin, the microbes that come from her nipple.

From here, a newborn’s insides begin to swarm with creatures — various families of bacteria, fungi, and more. And though it’s a biodiverse package, some microbes will have more to eat than others in the months to come and will enjoy a growth advantage over their competitors.

The populations of two groups, the lactic acid bacteria and Bifidobacteria — seeded via the mother’s colon and vagina — prosper as their environment gets flooded with nutrients from the newborn’s milky diet. While the lactose and milk proteins feed the baby, the other complex carbs that escape digestion go on to fertilise these bacterial groups and help them dominate the developing microbiome.

Months later and to the teary dismay of the teat-loving tot and their milk-hungry microbes, weaning begins. The infant moves onto solid foods and the amount of complex milk carbohydrates drops off. The microbes that thrived on milk, the dominant groups in the gloomy ecosystem of the gut, become less able to replicate. In their place, the meek begin to inherit the turf — bacteria also inherited from the mother and previously suppressed by the milk-loving microbes begin to dominate, feeding on the fermentable carbohydrates from the infant’s changing diet.

At about 12 months, an infant’s gut terrarium roughly resembles an adult’s. The ecosystem reaches an equilibrium of sorts — a stable climate, biodiverse with populations in check, but an equilibrium punctuated by chaotic bouts of stomach bugs and antibiotic carpet bombing.

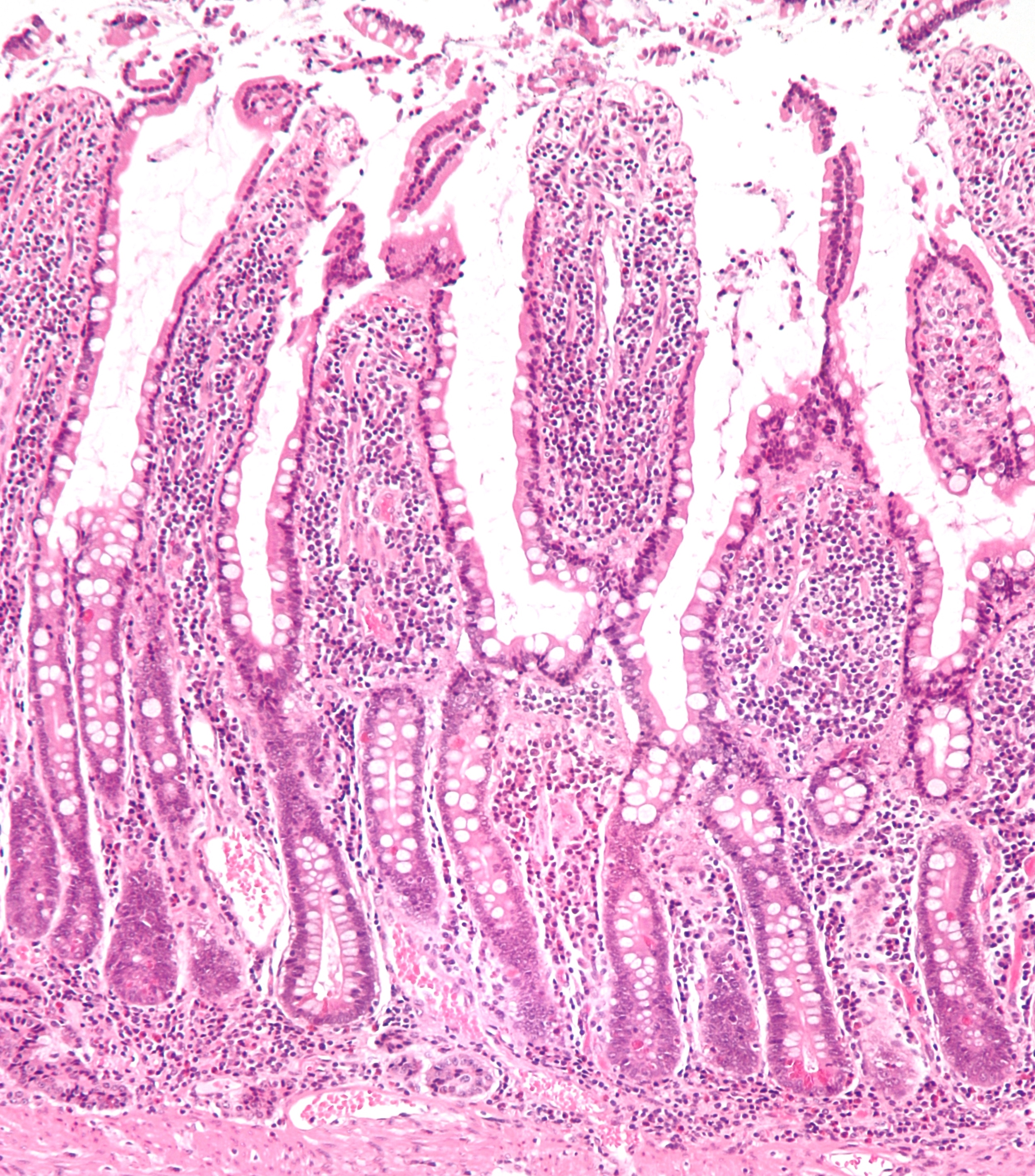

Home is where the heart is. And for our microbial species — the intestines are home. Here are 'villi', the intestines' finger-like projections lining our inside skin. Image: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0.

After a stomach bug, when the North and South Poles of the microbe’s world have ceased erupting, flora numbers are reduced but still diverse. It’s after antibiotics that the most significant changes take place. Some species are hit much harder than others, and where some areas of the gut were previously occupied and impenetrable, antibiotics make these areas vulnerable to occupation by different types of microbes.

And this is where fermented foods come into their own. Enter: Petite Miam, it’s French for ‘yum’.

Remember Lactobacillus? Those bacteria would eat lactose in milk and excrete (poop) lactic acid and short chain fatty acids. Well that is fermentation. It’s how some microbes feed. These food acids excreted by Lactobacillus are tart and are what give yoghurt its distinctive tang.

Apart from making tasty by-products, those bacteria are essentially pre-digesting our food for us (like a wack single-celled mamma bird), which allows us to ultimately extract more nutrients. And while these acids taste tart and delicious to us, they’re lethal for many types of microbes. They will fry.

Herein lies the beauty of fermentables like sauerkraut. Using fermentation, we can get a) a tastier food, b) a healthier food, and c) a food that lasts inordinately longer — all from something like cabbage, which would otherwise rot its lacklustre head away in days.

Fermentation is nature’s refrigerator, spice kitchen, and Nutribullet all in one.

When we ingest fermented products — gin, kimchi, merlot, miso, a pickle, or baguette — we’re not only eating the products of those hard-working microbes but also those hard-working microbes themselves! We’re taking their digestive process and putting it in our own digestive process.

Lactic acid bacteria Oenococcus turning tricks with grapes, fermenting acids and being vital to the production of wine 'n that. Image: Public Domain.

By the way, when these microbes eat complex foods like beans (beans the musical fruit), they emit gas, too. When a sufficient atmosphere of these gases builds up, we get an internal change of air pressure as the climate equilibrates. Aaaaand that’s a fart. So don’t be embarrassed next time you toot, for it was not you, it was your food (or at least the ecosystem inside you).

Returning to the scorched belly terrarium that follows a course of antibiotics, we know to eat probiotics like yoghurt. This is a land bridge, taking a continent of yoghurt species and introducing it to the foreign land of the gut. And while probiotics provide an instant hit of microbes and nutrients straight after a course of antibiotics, they’re not the be-all-and-end-all as our gut has a natural tendency to rejig itself.

Once re-populated your internal ecosystem of over one thousand bacterial species and 40 trillion clueless lives weighs around 1 – 2.2 kg — which, if you wanted to know, is the equivalent of a Chihuahua.

So next time you’re feeling lonely or bored, think of the cultures inside you, and why not crunch a pickle and relish a new dawn rising.

With assistance from Dr. Trevor Lockett, Food & Nutrition. For more info on our microbiome, including animations, visit our Hungry Microbiome project.

Feature image from Flickr/Sonny Abesamis, and the piece is republished from blog.csiro.au.