The Sun sets on our voyage. Note the majestic lone booby atop the mast. Photo: Katie Walters

It’s been a big two days, readers. Yesterday morning around 1am we found the wreck of SS Macumba lying 40 metres under the Arafura Sea, where she’s been since a Japanese aircraft strike in 1943. From the day of discovery till now, it’s been a flurry of media activity, satellite calls, Dropboxes, interviews, but now I’m free to catch you up on it all! It’s a long read, so get comfortable.

As I mentioned in my first blog, we’re on a ‘transit voyage’, not a research voyage. Our primary objective was to get Investigator from Sydney to Broome where it will begin its next research voyage. It’s like the commute to work. Having said that, we’ve done a lot of great research anyway, because that’s what Investigator does.

Booby mayhem and marine phenomena

Bumbling boobies abound bundled abreast, bound for Broome. Photo: Eric Woehler.

Circumnavigating the top half of our coastline is a unique experience not just for us, but for science. There are scarce data for our tropical waters and the species that inhabit them, so at each turn we didn’t know what to expect. It’s been described by Dr Eric Woehler, our resident ornithologist and leading seabird fanboy, as ‘a voyage of discovery’.

Given such fertile territory for discovery, Eric sat on deck seven, Monkey Island, from sunrise to sunset for the last 11 days straight, logging every single animal that has moved near the ship. Helping out are a faithful handful of the team, all marine life-enthusiasts whom I’ll get to soon. Our system on-board is such that Eric spots a species, logs its distance, abundance, and behaviour into software, to which Investigator instantly adds its own data — the current temperature, salinity, location, time, and fluorescence (amount of plankton). Together, these data can link conditions in the ocean to the species that manifest in this spot. Warm, salty upwelling, leads to fish, leads to predators, leads to spotting seabirds. This way we can link Australian food webs in the context of our environment.

Today Eric rose at 5:49am, watched and noted marine life until 7am where he tag-teamed one of the team to look out while he dashed off to a speedy breakfast before returning to the look out. This process repeats until 7:01pm each day, for two weeks. Some days are quieter than others, but as Eric points out: ‘There’s a big difference between a quiet day and a boring day’. And some days there are animals everywhere. We’ve seen:

- Thirty red-footed (blue-faced) boobies toppled atop RV Investigator’s foremast like feathered artists coating the mast and the ground below with white, purple, and black. The black poo is squid ink. Needless to say, our aerosol researcher, Morgane, wasn’t too happy with the boobies sitting on her ventilation intake. By the way, note the two sat perched on the left and right weather vane wind sensors, which were rotating slowly in the breeze, circle after circle. One especial boob of a booby just beneath these sensors had to duck each time the arm revolved overhead. At 1am the morning after, I rolled over in bed to check the rolling foremast footage, inky black except small lights illuminating the 30 snoozing boobies from below, two dimly-lit shapes still revolving in the dark.

- If that day on the mast was boobies packed like sardines, the next day had the inverse: flying fish like sparrows being chased through the air by seabirds in a feeding frenzy. Yes like some type of Inception-David Attenborough mash-up, I watched winged fish pivoting and dive-bombing over the winds away from gammy blue-faced birds. The flying fish ranged from 30 cm or so, to tiny little things the size of fingers. You’d see a ripple, then a grasshopper fly from the water only to realise it was a bird, no a plane, no a flying fish!

- And then the team observed a few dozen interactions they believe are the first for Australian waters: an ecological fish sandwich. From up on the monkey bridge, the team spotted the ocean surface roiling with bait fish, leaping and splashing. These bait fish, normally deeper, were being driven upwards by predatory tuna that find it easier to catch prey at the surface where prey have their backs against the wall (of the sky). With no choice, the fish were flinging themselves into the air to escape the jaws of tuna below, when, unfortunately for the fish, the boobies and shearwaters showed up. These birds aren’t afraid to get their feet wet and began dive-bombing the hapless bait fish like spears from above. Talk about caught between a rock and a hard place. Oh, and then sharks showed up.

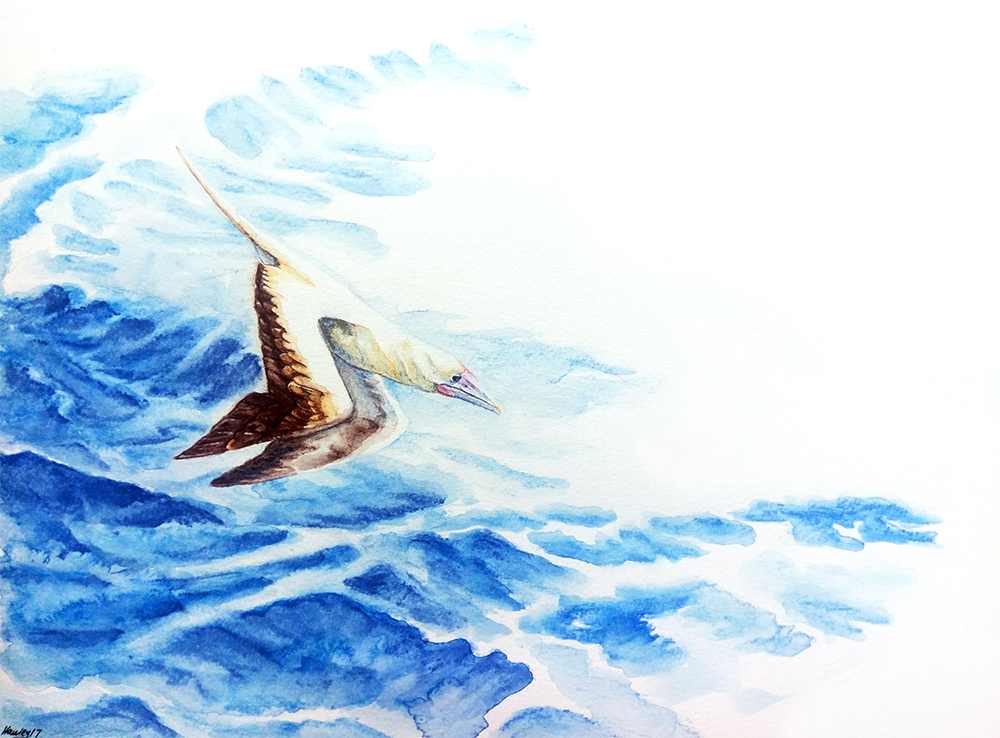

A red-footed booby folding in its wings, preparing to dive for a flying fish. Watercolour pencil. Based on a photo from Eric Woehler.

Eric’s helpers included Frances — RV Investigator’s hydrographer, adding geographic data to the search, Dr Ben Arthur — former Honours student of Eric and also lead on the Educator on Board program which hosted the other two bird-lookout helpers, STEM teachers Chris Halverson and Chantelle Cook. That was a segue to…

Educators on Board; teachers on a ship

Chantelle is a primary school teacher, and Chris is a secondary science teacher, and they’ve plunged into the science on this voyage like boobies to a bait ball. They’ve stayed up till the early hours of the morning to lend a hand on research, attended around a dozen talks and tours from the specialists aboard, scribbling assiduously. They’ve done a live cross to a STEM teachers’ conference in Darwin and crossed to science classrooms around the country, passing on the lifetimes of collected wisdom from the talent aboard. And every moment has been noted and photographed to take it all back to the classroom for the next generation of Investigator researchers.

Late night science. Here the team is awake at 1am or so doing a sediment grab off the side before deploying the ‘CPR’, Continuous Plankton Recorder, a type of reverse pianola where the notes are microorganisms. Left to right: Katie, teachers: Chantelle and Chris, Ben, and Linda.

I spoke with both of them just now about their plans and experiences. ‘In terms of science,’ said Chantelle, ‘I’ve learned more in one week than I have in my whole life.’ She plans to take her experiences and turn them into activities for her classroom, to give her kids critical thinking skills. ‘For us as teachers, it’s not just about building knowledge, it’s about building passion and enquiry in students. What they need for their future isn’t just knowledge, but how to collaborate and problem solve.’

Chris, a science graduate himself, has been working to create classroom exercises that use real data, ocean temperature, fluorescence, and also observations of bird numbers, and challenge his students to form hypotheses — possible stories — to connect them. He’s also keen to impart the interconnectedness of the sciences, land and marine ecology, geology and chemistry, and the researchers themselves: ‘I most enjoyed the interplay between the scientists – bouncing off each other. Science isn’t an isolated event. It works best when it’s combined. Seeing everyone swapping ideas, not putting any down, just expanding thought sequences. This is the first time, in a long time, I’ve actually seen that happen and I’m really impressed.’

SS Macumba

On Friday 6 August 1943, SS Macumba was steaming through the Arafura Sea carrying supplies for the war effort in Darwin when two Japanese aircraft came in low and opened fire on the vessel. Three members of the crew were killed in the attack, and Macumba took enough damage to the engine room that it began to sink. Disappearing below the waves, the vessel wasn’t to be seen for 74 years. (For more of the story, read our blog.)

The merchant ship, Macumba, after it was hit. Many survivors were saved via life boats (foreground).

One of the many projects planned for this transit was to search for the wreck of Steam Ship Macumba while passing through the Arafura Sea. Over the decades a number of parties, including the Navy, have chipped away at the search area, narrowing the location of her final resting place. Coordinating with those that had gone before us, we had a search area of 6.5 km by 3.5 km. It was divided up into a grid of 29 ‘lanes’ that we were going to traverse over 6-12 hours.

So it was, on Tuesday afternoon in the designated search area around 1pm, we began our ‘lawn mowing’ as it was called – going up and down the lanes. I set up a webcam to capture the search. In the second half, you can see the sun setting on our venture.

Were we going to find? Was it a lost cause? The growing schism of enthusiasm and cynicism got the crew bubbling with anticipation. And then the 12 hour count-down began. The action all happened downstairs in the appropriately named Operations Room, where the hydrographers searched the seafloor with Investigator’s sophisticated multibeam sonar.

The search continued late into the night. I was tasked with capturing the moment on camera, which I stood behind for sometime, lens trained on the monitors as the ship completed lap after lap, searching. (Each lap took around 20 minutes.) Towards the end of one of the laps, on the turn, we saw strange divots dotting the seabed, 40 metres down and spaced regularly. Each divot was a few metres wide and deep. The first sighting elicited a few passing comments, nothing more. Forty minutes later, Investigator’s multibeam returned, revealing a larger field of divots. We got talking. Eric, the ornithologist, suggested it was debris. We knew the seabed here was largely muddy and soft, and debris could very well have created such a pock-marked field. Growing ever-sleepier, I waited another two laps for the multibeam to return and reveal more mysterious seabed, and discovered….nothing. I went to bed.

Two laps later, on the ship’s return, Amy, the hydrographer, and Eric, called the bridge and asked if this lap they could take an extra wide turn, since the divots weren’t actually on our search grid. Heeding the request, the deck officers took the ship out off the grid, letting the multibeam return images of the extent of the red and orange divots, and then among them, a luminous white rectangle. ‘Oh my god!’ ‘Ahh!’ ‘That’s a ship!’ ‘…That’s a ship.’ Both teachers, researcher Katie, and Amy were the first to see SS Macumba in over 70 years, and boy were they excited. (We might release the footage later.)

Pock marks might be below-the-seabed methane traps set off by the initial impact of the falling ship, which released gas up through the mud. Very much a multi-spout whoopee cushion.

I woke, wandered upstairs and saw the TV monitor in the mess, a map with the ship’s path and a line showing where we’d been overnight — a tight nest of criss-crossing figure eights over and over a small point off the search grid. We’d found it, alright.

And it was from this point, for two days, that I was lost in work, compiling footage, editing clips, fielding calls and requests, photos and audio, and responding to emails in the Operations Room, like some type of subterranean computer-savvy insect larva, to emerge…

Timor Sea, science communication, and farewell

A slight breeze rippled through just as I took this shot, creating ‘sandy dune’ patterns on the water. Before and after the breeze was bizarre. For scale, spot the jellyfish.

Finally, this afternoon around 4 o’clock, I stepped out into daylight for the first time in some time, but something seemed wrong. My first thought was that I’d been in front of a computer screen, behind a camera, or staring at cream walls waiting for files to upload for so many hours that I’d forgotten what reality looked like, because it didn’t look right.

Our office. Left: Linda; Middle: Katie; Right: Me, writing the blog you’re reading. Photo: Katie Walters.

We were sailing in the Timor Sea, just off the coast of Darwin, and though we’d been in the tropics for over a week, the air had a strange character. It was at skin temperature, like it wasn’t there, which gave me the curious sensation of having no separation from inside to outside my body. The water looked all wrong, too. Maybe because of the clouds or the strange haze, but it looked digital, like poorly rendered CGI, too few polygons interacting all wrong. Investigator had strayed into waters from an early PlayStation game. As I climbed the stairs up and around the ship it acquired more unusual characteristics. From this height it formed simple glassy mounds that roved past the ship, sometimes hitting the stern and flattening to fixed shapes that spun away. Towards the horizon the ocean grew hazy and misted into the clouds above. I reached the fifth deck and Katie, our marine social scientist, spun around and lowered her camera, ‘Are we in a parallel reality?’ she asked, ‘it feels like we’re going to sail off the planet’. We gushed about being in a dream sequence or limbo, since our points of reference, the ocean, sky, horizon, were all askew. For the next 90 minutes we stood at the railing, transfixed at the fake water.

Katie’s a marine social scientist, about to begin her PhD on communication, the communication between marine scientists and you, the public. What does the public think of science, the findings of science, and the people who conduct it? Do they stay abreast, do they listen, do they care? And why not? Katie’s background is in science, and the arts. On the ship she’s using different types of storytelling to share the findings of science with those outside the sphere, testing effectiveness. Out of all the work on the ship, hers is most closely aligned with mine, as well as my passions. The findings of marine science, any science, present the path to preserving the things we value most, as well as the things we take for granted: our drinking water, our increasingly silent ocean, our hot sky.

Our last sunset aboard RV Investigator and it was a beautiful one. On the last few nights we’d gather outside and watch the Sun go down, desserts in hand, looking for the infamous green flash, and await the rising moon. Photo: Katie Walters.

Standing at those railings watching the waves below, Katie and I saw a trend in the animals drifting past, and became armchair ecologists. We watched the glassy waves like foothills rub along the hull, swelling, sharpening their peaks to mountain ranges that would hold for a moment, before splitting at a point or two along their crest, unzipping to meet up, shattering all the way to spill white froth on the next wave coming through. There were jellyfish carried in the waves. Close-up they looked like helmets filled with tentacles of amber broccoli, but at a distance, all together, berries frozen in a trifle. A few minutes later, in the toy water, a bobbing shape broke the surface, and it was a green turtle (turdle). It swam slowly, and as it approached, I saw it had just pooped. Small eddies of poop spiralled in the wake of its flippers and it didn’t seem to care.

Confused about the scale? I took this shot some 15 metres from the surface, yet it looks at eye level.

Flying fish were the gift that kept on giving and this was doubly true on this waveless afternoon when the surface was a mirror for the cloud formations above. The sky’s perfect reflection was only broken when a fish would shoot up from below, leaving the glass surface with a trailing footprint like a sinusoidal S, each of the bends looping out into concentric circles, small at first, then growing into a stream that echoed in the reflected clouds. They’d swim on the surface runway for a few metres then lift into the air and glide for a hundred metres or so till they were a tiny skipping stone that disappeared behind a distant ripple.

Sometime later I was taking a panorama, trying to capture the blueness, and caught a cream colour in the corner of my eye. I looked down and saw my first shark. It was around a metre and a half long, gliding as if in free-fall alongside the ship, moving its tail casually, going through the motions for show. In a ‘boy who cried wolf’ scenario, I said ‘shark, shark’, but scepticism got the better of my deck mates who missed the delightful thing. And thus our trend for animal patterns was formed: Jelly, turtle, shark, jelly, turtle…shark! (This sequence happened at least twice.)

We’re not sure why the sea was so funny-looking that afternoon. Each day I get up and look out and its personality is different. In fact, most things are different each day, always surprising. I’ve learned too much to ever write down or pass on entirely, and I’ve only been on the ship for a fortnight. The researchers and crew that come on and off Investigator are sometimes at sea for eight week stints and have research experience stretching back decades. Their diversity of knowledge and relationship with the equipment on-board is overwhelming, which is just as well given the numbing complexity of the ocean system, the atmosphere, and the land and life that feeds into it. If we’re to conserve these precious things, we have to understand them through science; only by coming together, communicating, and cooperating can we do that effectively, and I’ve seen no better instance than on my trip with Investigator.