This year I got the opportunity to paint two artworks for an upcoming book entitled Secret Lives of Carnivorous Marsupials. As the title suggests, the book tells the story of the world's carnivorous marsupials: their diversity, biology, behaviour, ecology, and more. Carnivorous marsupials include furry, pouched meat eaters like Tasmanian devils and Tasmanian tigers, quolls, and also the more delicate and adorable predators like the dunnart and antechinus. I worked on artworks for the chapter on extinct marsupial carnivores. The two species I studied and painted were the marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, and the marsupial sabretooth, Thylacosmilus atrox. Below are the two paintings in reduced resolution.

I thought a nice introduction to the alien ferocity of both species would be a break down of the etymology of their species names.

Thylacoleo carnifex — the marsupial lion

My 'supes. Copyright Jesse Hawley.

"A skeleton of a Marsupial Lion (Thylacoleo carnifex) in the Victoria Fossil Cave, Naracoorte Caves National Park." Wikicommons.

"Mounted display of Thylacoleo carnifex at the Wonambi Fossil Centre, Naracoorte Caves National Park, South Australia." Wikicommons.

The animal — Thylacoleo carnifex

Thylaco (from Greek thylakos, meaning pouch) + leo (Latin, lion) + carnifex (Latin, butcher or executioner).

Yes, that is a pretty gnarly species name: the pouched lion that executes. The marsupial lion stalked Australian grasses around 50 000 years ago and would likely have co-existed with Indigenous Australians. They were the pit bull equivalent of the marsupial world: squat, robust, and carrying jaw power like secateurs. In fact, relative to their size, the marsupial lion is estimated to have had the strongest bite of any mammal ever. A 100 kg marsupial lion would have had a bite as strong as a 250 kg African lion. Pretty amazing for a marsupial just 75 cm tall and 150 cm long. Though they are extinct, their closest modern relatives are herbivorous marsupials like wombats and kangaroos. It's thought that the marsupial lion's ancestors were themselves herbivorous. Herbivores use their molars — large, flattened teeth inside their cheeks — to shear and grind up fibrous plant material. Ancestors of the marsupial lion, it seems, had such grinding teeth, but over the course of evolving into meat-eating terrors, these molars adapted into blades that sliced through flesh instead. The marsupial lion's incisors — the front 'rat-like' teeth — jutted out from the mouth, almost beak-like. It's thought these were used by the lion to pluck hunks of muscle from their prey during a take-down, inflicting death from blood loss and trauma.

A typical 'placental' carnivore like a tiger or wolf would kill their prey with their canine teeth — the pointy ones fetishised by vampirophiles. Interestingly, the canine teeth of marsupial lions are so reduced, they're almost absent. They either look like persistent milk teeth or are just gaps. To justify their Latin name even further, the front paws of marsupial lions had thumbs which were semi-opposable and hooked. They may have used these thumbs as digital ice picks, hooking into large unyielding prey while the jaws hacked away. The vertebrae, backbone components, in the lions' tail, too, have joints similar to those of kangaroos. It's speculated they used their tails as a temporary 'prop', allowing the lion to rear up and gain extra height for stretched strikes. Though this is just speculation, a quick squiz around YouTube reveals that predators use their bodies for extraordinary and unpredictable applications, so I wouldn't be surprised if the tail prop was a reality.

Cave painting image from Antiquity.ac.uk

The art

As mentioned, marsupial lions are most closely related to the group of marsupials which includes kangaroos and wombats. Though interesting, it's not particularly helpful in choosing the markings or coat type the animals may have had in their life time. I instead looked to marsupials with similar lifestyles and habitats: quolls, and Tasmanian tigers and devils. It is thought that the marsupial lion was a stalking predator, and thus would have needed a coat to break up its outline. Lines and spots are popular choices for carnivores. In 2009 there was a cave painting found in the outback that depicts a large predatory marsupial. Experts think it likely depicts a Tasmanian tiger, which previously roamed the entire continent. I particularly liked the depiction and noticed the prominent head and cocked forearm. A big head and big arms were pretty characteristic of marsupial lions, so I eschewed the experts opinion and fancied the painting as a marsupial lion, and not tiger. I therefore decided to pop stripes on 'em. And — unlike the tigers — this depiction had stripes that extended not just up the rump, but also up the spine to the shoulders.

I got really excited one time imagining marsupial lions as giant, horrific brushtail possums. If you've ever walked past a gum tree at dusk and heard the snuffling and screeching of embattled possums, you'll know how startling those guys can be. I wanted to capture some desperate, snarl-off between two creatures, so that's the scene I chose for my lions. I also modelled my colour scheme off the brushtails.

Above-left is my colour scheme mock-up. I didn't want a plain old grey coat, so I tried to make it a little rusty like kangaroos and many other marsupials. Their coat isn't one-flush colour, but a salt and pepper set up. I quite liked the idea of the sooty eyemask and tail, so I factored that in in my mock-up, but looking at the final, I kind of forgot about it, sadly. Looking at quolls, they have fair, pinkish, almost delicate noses, ears, and hands. I incorporated this with my lions, since I wanted that same adorable vulnerability to the Australian sun. On the above-right mock-up, I had the right lion pulling a layer of muscle from the kangaroo's ribcage. This was supposed to go into the final, but I accidentally positioned the jaws too wide for this. I instead changed the lion's pose into a protective one, like a dog snarling over its bowl of dried pellets. Finally, I was planning on having a sun-set scene, rich with the mellow yellows and oranges of dusk, but I thought that might a) obfuscate the depiction/colour scheme of the subject, and b) be too hard for a n00b meister like myself.

I actually did this illustration after finishing up the marsupial project and writing this blog entry. Evidently I still had the marsupial lion on my mind and wasn't quite pleased with the painted products. It might look like pen, but it was actually drawn on a tablet. Interestingly, while the commissioned paintings took me some months, this one took just a single sitting in the park...

Thylacosmilus atrox — the marsupial sabretooth

My interpretation of the marsupial sabretooth. Copyright Jesse Hawley.

The animal — Thylacosmilus atrox

Another 'Thylaco' (pouched) + 'smilus' (Greek, dagger) + atrox (Latin, cruel/frightful).

The cruel and pouched dagger, another grisly species name for another amazing animal. Thylacosmilus atrox, also known as the marsupial sabretooth (for obvious reasons), is a carnivorous mammal that lived in Argentina and other areas of South America. It is not a 'marsupial' per se, but part of a broader group 'metatheria' that describes mammals around before things were less clear cut, evolutionarily speaking. Also, it's not related to the 'placental' sabretooth (the cat-variety and pop culture hussy). Their frightful teef evolved independently. This species went extinct millions of years before the 'sabretooth tiger' or smilodon reared their fanged head.

The marsupial sabretooth's head was bizarre. Where smilodon grew their sabre-like teeth from canines embedded in their top jaw, these 'marsupial' sabretooths grew them from the same spot, but with roots that grew up into the skull and became embedded behind the eye sockets. Whaaa? In the image below you can see the bulbous root canals curving up, between the nose and eye, and resting almost near the back of the skull, making toothaches and headaches indistinguishable.

"Four million year old skull of Thylacosmilus atrox, a saber-toothed marsupial meat eater from South America. Picture taken at the American Museum of Natural History." Wikicommons.

Another weird thing you might notice from this creature, is the lower jaw. In smilodon, the canines jut from the mouth and hang there, like someone putting drinking straws under their lips. These marsupial sabretooths, however, came up with an even sillier, albeit safer, arrangement. Their chin grew down 'in-between' the huge teeth and acted like a scabbard or buffer. This way, if a defensive prey item were to swipe at the teeth from the side, they'd be protected by the chin, airbag style.

UNSW and Dr Stephen Wroe.

Not only was it comically bummish, but that chin could swing, baby. The image at left compares two skulls coloured yellow: A) smilodon at left and B) marsupial sabretooth at right. The marsupial could swing its lower jaw majorly.

The marsupial sabretooth wasn't that large an animal, about the size of a jaguar. But even so, its bite force was negligible — about the clamp-down clout of a house cat. This would be a problem if the marsupial sabretooth killed its prey by clamping its jaws shut, but this isn't the way scientists think it killed.

"Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio". Wikicommons.

Looking at the fossils fighting, you can see the large arcing neck of Thylacosmilus atrox. This neck was supported by bulky neck muscles that could throw that head around like it weighed nothing. If a typical carnivore is a murderer with giant scissors to clamp and cut the victim, then the marsupial sabretooth is a murderer with a knife, swinging down to stab the victim in the neck or side. The idea is that during an attack, T. atrox's lower jaw would swing out of the way, and then the powerful neck muscles would drive the head and sabre-bearing upper jaw down into the prey, puncturing deep. Here, a strong neck mattered much more than a strong jaw. You don't need a strong thumb to stab someone with a dagger.

The art

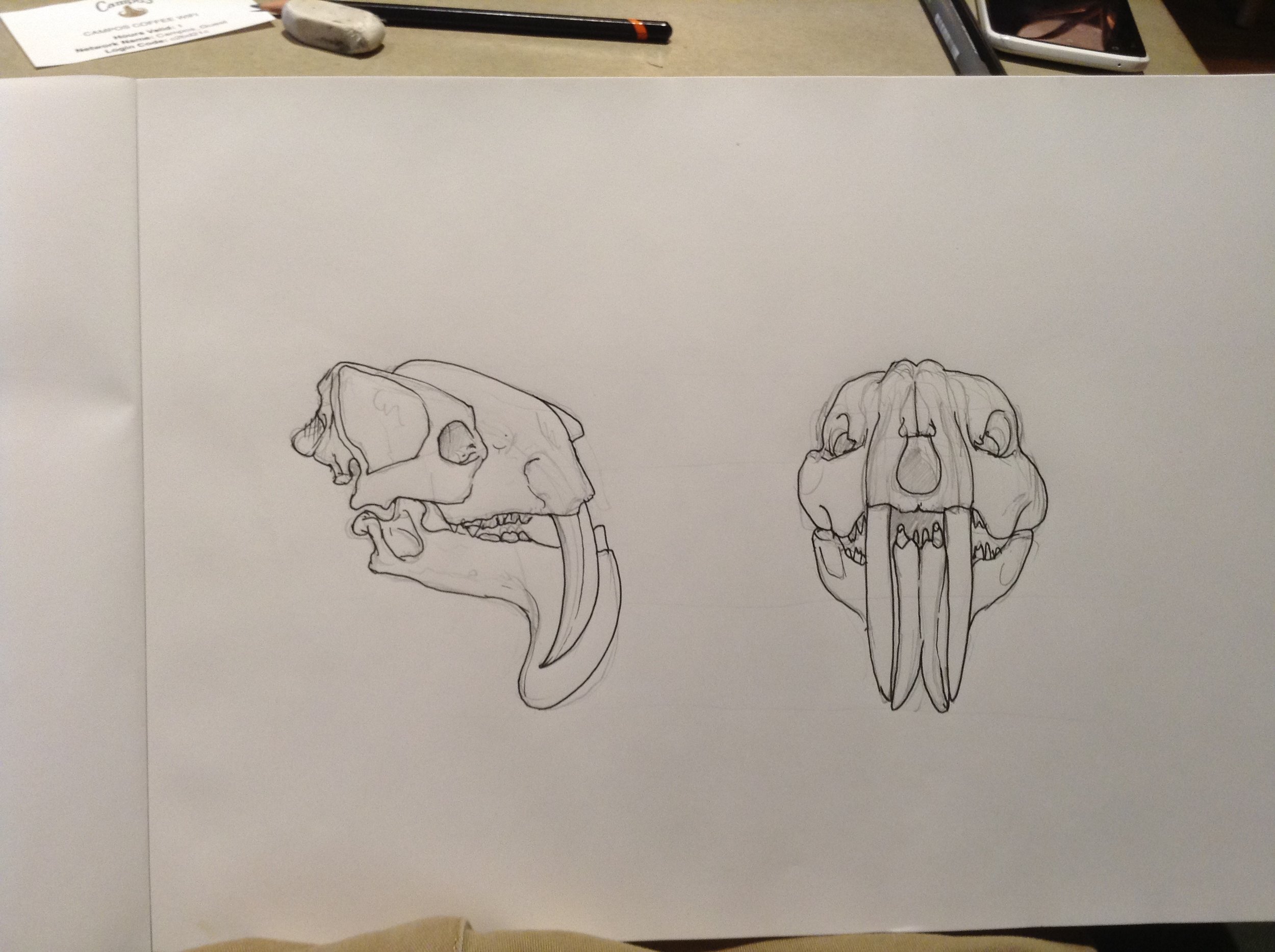

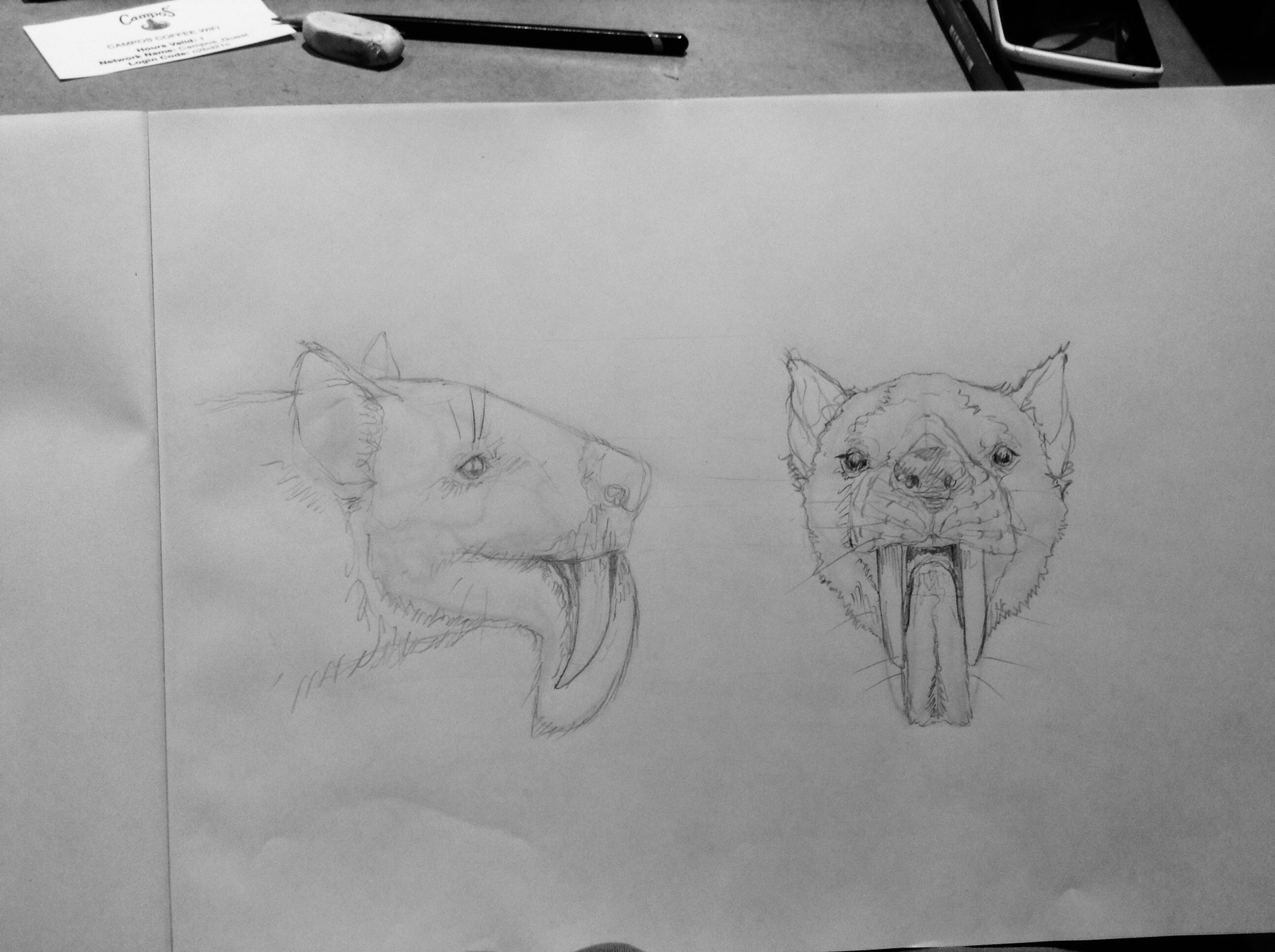

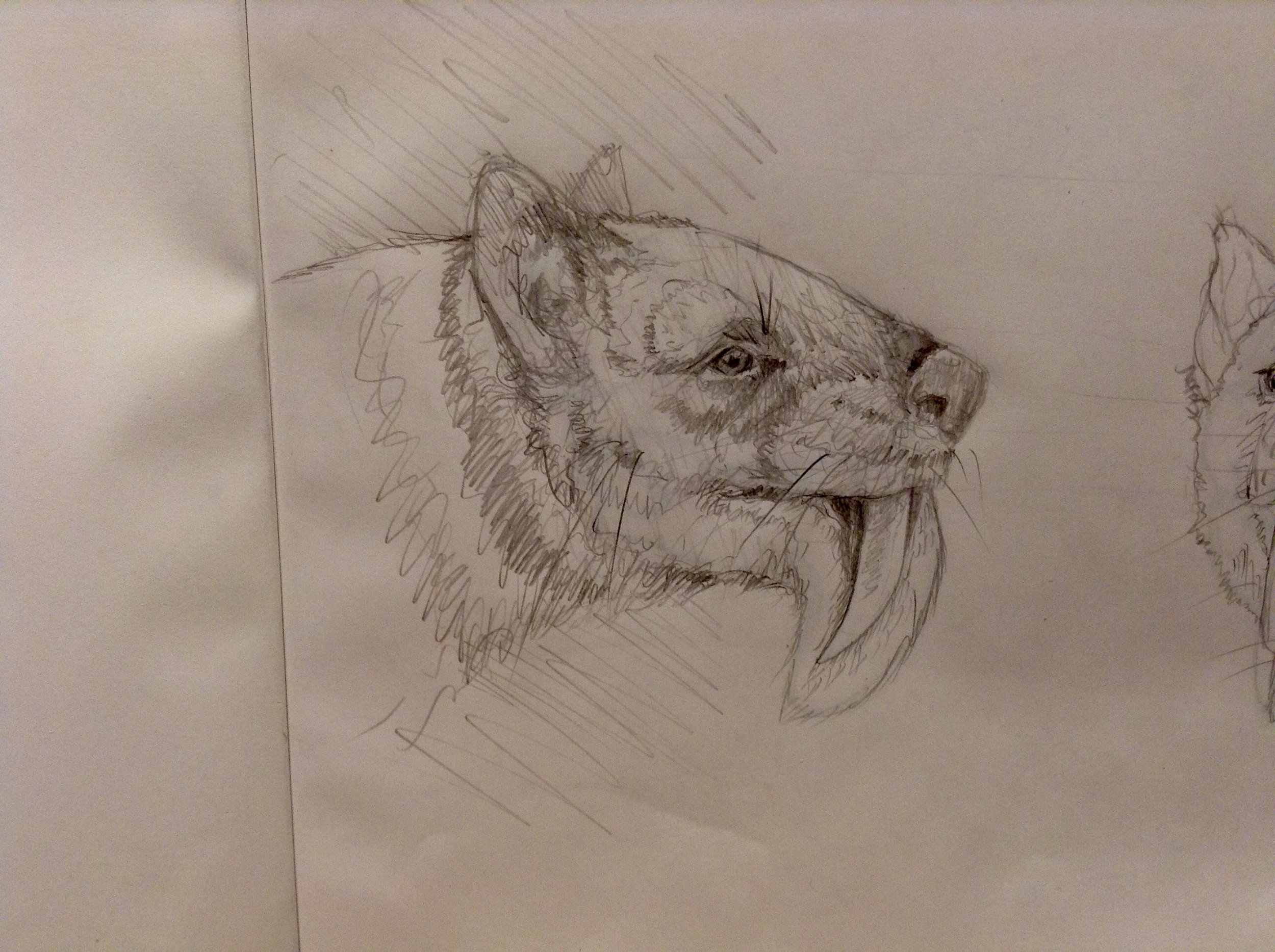

Aesthetically, I wasn't overly happy with my first painting, the marsupial lions. The image didn't really grab me visually, wasn't too coherent, and has some things wrong with it that I'm not experienced enough to identify. With this one then, I aimed to make it visually appealing first. The carousel at left is my drawings of T. atrox's skull from the side and front. Using the same drawing, I overlaid its facade, and then did some facial markings that looked pretty, modelled off an African civet. I felt it had a bit of personality at this stage.

I then took this face, which I was pleased with, and fashioned a body based on the skeleton. From here, I decided on the scene.

The marsupial lion artwork was very graphic. Capturing food is irrelevant in evolution's eyes unless there's reproduction and child-rearing in the mix. Since marsupials share 'a pouch', I wanted a softer, more maternal scene contrasting with the subject's intimidating fangs.

I wanted to depict a mother T. atrox carrying a joey through the wilderness, stopping on a log to smell the air for threats — something you might see in a kangaroo documentary. I was pleased with the idea, so I modelled the body pose and then picked a colour scheme. It's here I made a pretty big error. Research suggests that T. atrox lived in savannas and sparsely forested habitats, and yet I placed my subject in what looks like pretty thick jungle. For this species, less is known, so I contacted the specialist to help provide advice for accuracy. She liked my drafts all the way up until I placed the animal on a log in the jungle. I also went against her advice of placing the pouch 'rear-facing' to placing it front-facing for convenience's sake. Sorry, Christine — it would have looked unsettling with a baby popping out the bum end.

Anyway, that's it for my illustration tales. It took a long time and was a very interesting learning exercise. For the marsupial lion, at least, I think I've read literally every single piece of research ever written about the animal. I also think it's my favourite now. The book, Secret Lives of Carnivorous Marsupials is published by CSIRO Publishing and comes out late 2017, early 2018, authored by Prof Chris Dickman and Dr Andrew Baker who I'm very grateful to for entrusting me with their work.